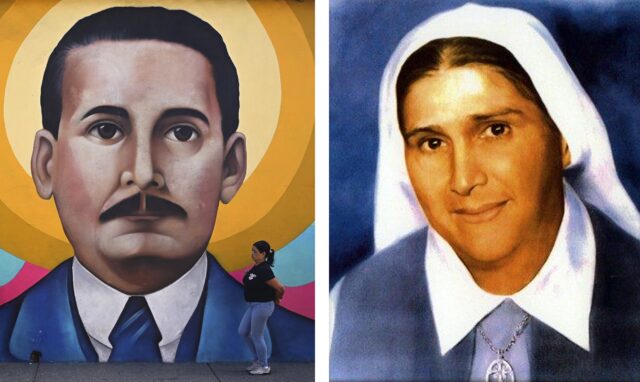

As Venezuelans await the upcoming canonization of the South American country’s first saints — Blessed José Gregório Hernández and Blessed María Carmen Elena Rendiles Martínez — both the church and the government prepare for the unprecedented event, promoting restoration works and planning the logistics of the several activities that will happen in Caracas and elsewhere.

President Nicolás Maduro’s government is collaborating closely with the Catholic Church on logistics and infrastructure. But some exiled priests warn that the regime is politicizing the event to boost its image.

Major celebrations are expected to happen in the nation’s capital and in the town of Isnotú, in Trujillo province, where José Gregório — as Venezuelans call him — known as the physician of the poor, was born in 1864. The most important popular piety saint among Venezuelans since his death in 1919, his canonization is being preceded by pilgrimages to his hometown and a series of cultural activities.

A front altar is being built by the government at Our Lady of the Rosary church, in the municipality of Rafael Rangel, where Isnotú is located. The church will receive most of the massive activities planned to happen before and after the canonization.

The sanctuary of the Christ Child of Isnotú is being renovated and air conditioners are being installed inside it. The local government is also creating a new park in Rafael Rangel. The idea, according to Trujillo’s governor Gerardo Márquez, is to embellish the future saint’s place of birth and to ensure there will be “adequate spaces for the religious celebrations.”

In Caracas, the local government has been working on the restoration of the church of Our Lady of Candelaria, where the remains of Blessed Hernández were placed. The works include structural reinforcement and aesthetic details, and the front square is being renovated as well. The future saint’s house, where a museum was created, is also being restored.

The church has been taking part in the coordination of those works and of the celebrations’ logistical planning with members of the government. On Aug. 7, President Maduro met with a church delegation in order to discuss the ceremonies.

As part of several festive activities leading to canonization, the mayor of Caracas, Carmen Melendez, was one among thousands of participants of the “Night Route for Peace,” in which faithful marched Oct. 4 from the church of the Divine Pastor, passed by Blessed Hernández’s house and by Vargas Hospital where he worked, and ended the procession at the Candelaria church. It is said Blessed Hernández would walk between those locations every day.

The joint effort of the church and of Maduro’s regime is not surprising, given the stature of Blessed Hernández. According to Francisco González Cruz, a geography professor at the University of the Valley of Momboy, in Trujillo, who authored many books about the future saint, “he’s the most famous Venezuelan ever.”

“Every Venezuelan knows Bolívar and José Gregório. Not everybody likes Bolívar, but everybody likes José Gregório,” he told OSV News of the two South American giants, including the father of independence of several South American states, Simón Bolívar.

Members of the opposition, especially priests who had to leave Venezuela, have been concerned about the political use of the canonization by Maduro.

Father Pedro Freitez, exiled in the United States, told OSV News that “the regime has sought to manipulate and exploit the canonization by every means possible.”

“They want to use it for purely political gains. They will put on many shows and spectacles,” he added.

Father José Palmar, who also lives in the United States, told OSV News that Maduro’s regime intends to use the canonization to “clean its face stained with theft, fraud, embezzlement and death.”

“But they will not be able to appropriate his holiness nor cover up their guilt with canonical incense,” Father Palmar declared. He has been calling the Venezuelan clergy to avoid being manipulated by the regime and put an end to any kind of “collusion” with the government.

While the church has been avoiding direct criticism of Maduro’s administration for years, it seems to be taking advantage of the occasion in order to put some pressure on the government.

On Oct. 7, the bishops’ conference released a letter saying that the canonization is a good occasion for the government to take “measures of grace” and release political prisoners.

Amid such political struggles, people like González have been worried about the deeper meaning of the canonization. For him, “José Gregório is a symbol of what every Venezuelan could be,” as he “had all the virtues we should pursue.”

A devout Catholic since childhood, Blessed Hernández was born in a somewhat prosperous time in Isnotú, when coffee was a valued crop.

“His father was a coffee grower and also a shop owner. He had a good teacher and lived with good people,” González described.

His father persuaded him to study medicine and his mother, who died when he was only 8, told him to get back to Isnotú after his graduation in order to treat the poor.

The future saint was a brilliant student. He went back to Isnotú, as he had promised to his mother, but a professor recommended him for a government scholarship in France. There, he studied experimental medicine and bacteriology with leading scientists. When he came back to Venezuela, he brought several novelties, including becoming one of the first doctors to work with microscopes in the country.

He taught at Universidad Central de Venezuela for years and kept an office where he took care of everybody, even if the patients didn’t have money to pay for their appointment.

“He charged the rich — of course, he had to make a living — but treated the poor for free. He would listen to all people very carefully. That’s how he became a master in diagnosing them,” González described.

An ardent Catholic, on two occasions he tried to abandon his life in Venezuela and become a monk in Europe. But diseases prevented him from pursuing such a path, and he had to return to Caracas.

The doctor of the poor was hit by a car as he was going to see a patient. His coffin was carried by numerous students and colleagues, gathering a great crowd.

The devotion to him would begin shortly later. In a sign of popular piety, people began giving his name to their sons. Images of him were seen everywhere.

The future saint incarnated the qualities needed for what Pope Francis called integral human development, González told OSV News.

“The canonization is only the beginning. We need to know him more and more deeply and to imitate him,” he said.