When bishops from Poland and Germany gather to commemorate one of Europe’s most famous acts of reconciliation, discussion will focus on its historic significance and continued meaning for the present.

“As tensions resurface today in the face of war, this great step between Poles and Germans, taken just 20 years after World War II, deserves to be remembered,” explained Archbishop Wojciech Polak, Poland’s Catholic Primate.

“As a heritage for rebuilding relations, it could also be of great value now, as we seek a common future based on renewed mutual acceptance.”

The Gniezno-based archbishop spoke ahead of Nov. 18 ceremonies in Wroclaw marking the 60th anniversary of a letter from Poland’s bishops to their German neighbors, which contained the words, “We grant and ask forgiveness.”

In an OSV News interview, he said the gesture had been misrepresented by Poland’s communist regime to “inflame animosity” toward the Catholic Church, and had required “patient explanation” to defuse public protests.

“We learn from this that forgiveness isn’t simply a question of exchanging relevant words — it involves whole relationships, and can prove very arduous,” Archbishop Polak told OSV News.

“In fostering reconciliation, the church doesn’t act in the name of the state, but appeals to deeper human experiences and sensitivities, which link us fraternally in a common humanity. If accepted and embraced, however, these deeper processes can also bear fruit in interstate relations.”

Poland lost a third of its national wealth and a fifth of its population, including 90% of its 3 million strong Jewish minority and a fifth of its Catholic clergy, under German Nazi occupation in 1939-1945.

The bishops’ letter, dispatched from Rome on Nov. 18, 1965, at the close of the Second Vatican Council, invited German church leaders to Poland’s upcoming Christian millennium, and said the Polish bishops were extending their hands in a “most Christian, yet very human spirit.”

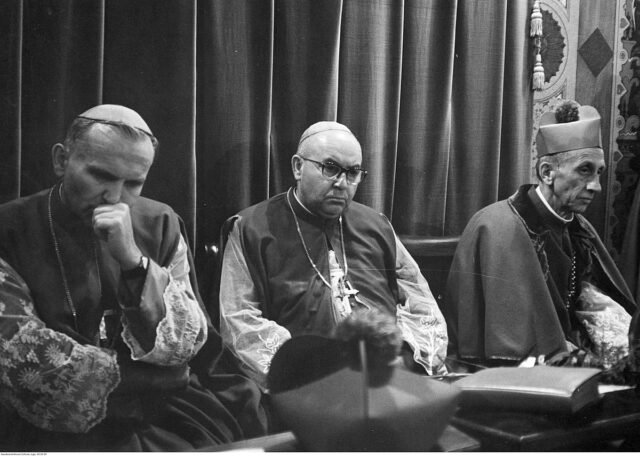

The nine-page letter, whose 36 signatories included Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Kraków, the future Pope John Paul II, recounted historic grievances but also highlighted the two countries’ shared Christian faith and controversially offered mutual forgiveness.

Although intended as a conciliatory gesture, the letter provoked angry accusations of betrayal from Poland’s ruling communists, who used it in a bid to undermine the Polish church during the 1966 millennium, for which German bishops were refused visas. The millennium marked Poland’s adoption of Christianity, in 966, as well as the 1,000th anniversary of the foundation of the Polish state.

A Catholic historian and former Polish senator, Jan Zaryn, said the letter contradicted the communist regime’s policy of “instrumentalizing post-war hatred” to cut Poland off from Western Europe, and of portraying the Soviet Union as sole guarantor of Poland’s territorial security.

He added that the anti-church “smear campaign” was facilitated by total communist control of the media, but said the regime, headed by Wladyslaw Gomulka, overreached in efforts to “slander and defame” the church’s leader, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski, who emerged as “unjustly suffering” at the hands of “communist manipulators.”

“On one hand, the bishops’ letter was a religious act of forgiveness, sent in a Christian spirit by devout Catholics,” Zaryn told OSV News.

“On the other hand, it also had a political context, as an attempt to ease Poland’s captivity behind the new Iron Curtain by seeking dialogue between neighboring Christian nations. The communists were well aware of this — they knew the church was fundamentally opposed to Europe’s long-term division.”

A four-page reply to the Polish letter, signed by 41 German bishops, was sent on Dec. 10, 1965, acknowledging “many atrocities” suffered by Poles, but also noting the war’s “difficult consequences” for Germany.

Although the German letter accepted the “outstretched hand” in aid of a “new beginning,” it disappointed some Polish prelates, including Archbishop Boleslaw Kominek of Wroclaw, the Polish church’s chief intermediary, who viewed it as too diplomatic and lacking contrition.

Germany improved relations following its 1990 reunification, backing Poland’s later accession to NATO and the European Union, while German church foundations such as Renovabis funded the rebuilding of Polish churches.

Tensions have periodically resurfaced, however, over compensation demands for the post-war mass expulsion of German civilians from western Poland, as well as over Polish calls for further German reparations, in addition to those made in the past, but hailed insufficient for gigantic losses of the Polish nation.

A 1947 estimate by Poland’s communist regime set the country’s wartime losses at $850 billion at current value, while a more recent estimate in 2022, under Poland’s previous Law and Justice government, put German reparations owed to Poles at $1.5 trillion.

Germany says Poland signed an agreement eight years after the war that reparations would cease from 1954. However, Polish Law and Justice leaders, now in opposition, insist the agreement was invalid, because it was signed by a communist government and facilitated between the USSR and communist-ruled East Germany.

“In this context, we should see the 1965 letter as offering a valuable model — of how to act truthfully as Christians in difficult conditions, in ways which don’t falsify or simplify reality,” Zaryn said.

Archbishop Polak told OSV News the 1965 letter reflected a “very particular relationship” between Poles and Germans, left by “deep war wounds,” but said “similar motives” had been at work in reconciliation efforts elsewhere.

He added that European unity had been assisted by other initiatives, including German-French friendship and efforts following the 1992-1995 Balkan War, but said Polish-German “forgiveness and reconciliation” had been “helpful and creative” in wider processes across the continent.

“Every such case is unique, making general evaluations difficult — but inspiration can certainly be derived from this epoch-defining gesture, in the conciliatory courage which arose in the hearts of Polish bishops and found echoes on the other side,” the Polish primate told OSV News.

“While I don’t know how much the Polish bishops expected from their prophetic openness, we can see how it later gained fulfillment in a growing Polish-German closeness.”

The 60th anniversary will be marked by Mass in Wroclaw’s Cathedral of St. John the Baptist and wreath-laying at a monument to Archbishop Kominek, who was made a cardinal in 1973, as well as by a new joint declaration by the Polish and German bishops’ conferences.

In a Nov. 5 website statement, the German bishops said the Poles’ “courageous gesture” stood as “an outstanding testament” to the “willingness of nations” to reconcile, and had “contributed significantly to changing the political dynamics in divided Europe.”

Asked whether the 1965 letter had contributed to the advent of Polish and German popes, Zaryn said the gesture had added to the Polish church’s “exceptional heritage,” which had been recognized as offering a “vibrant prescription” for the church worldwide at St. John Paul II’s election in 1978.

“As early as 1965, the then-Archbishop Wojtyla spoke of a distinction between remembering and forgiving, noting how forgiveness doesn’t erase memory but creates a space for us to move forward,” Archbishop Polak added.

“Though they’ll encounter difficulties, forgiveness and reconciliation are always possible — if enough people believe in them and have the courage to confront their fears and resentments,” he told OSV News.